JUSTICE PALACE RIYADH

The project addresses the problem of urban space in the centre of a modern metropolis, and is acknowledged more for its role in urban development than for its architectural quality. Intended to revitalize the centre of Riyadh, the program consists of a variety of functions around a mosque, a typical pattern in Muslim societies.

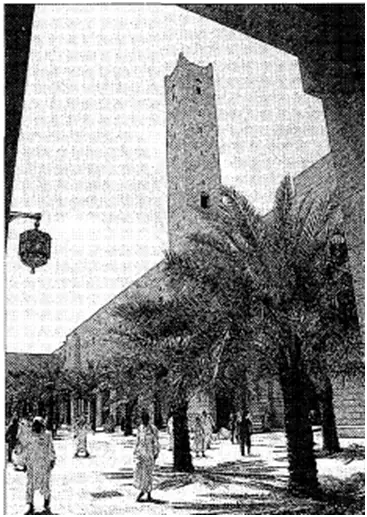

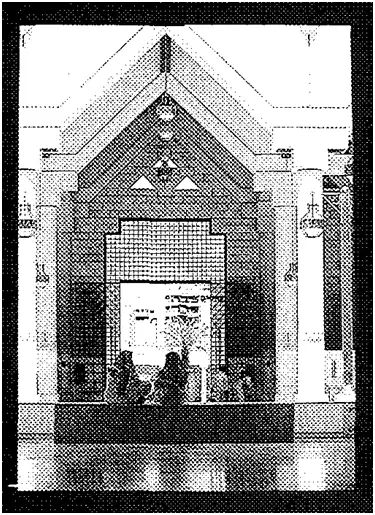

The architect has met the complex demands of a new program on an old site with a solution that responds to the local lifestyle, climate and physical surroundings. The spatial character and iconography of the project provide a sense of continuity with the historical context, and the reinterpretation of the language of traditional Najdi architecture demonstrates a mastery of building techniques and a deep understanding of the culture of the area. The use of modern materials and technology, such as air conditioning, is unobtrusive and does not detract from the quiet sense of spirituality inside the mosque.

The sequence of open courtyards is skilful and sensitive. The architect’s success in creating a modern urban complex while retaining the essence of its traditional frame is a remarkable achievement. The sustained efforts and commitment of the clients, the Arriyadh Development Authority, are especially noteworthy, and point towards the essential role that informed clients can play in the creation of architecture and urban environments.

PROJECT : KASR AL HOKM- JUSTICE PALACE

CLIENT: ARRIYADH DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY

ARCHITECT: RASEM BADRAM

URBAN DESIGNER/ PLANNER : ALI SHUAIBI AND SALEH AL-HATHLOUL

Phasing:

This project was conceived in two distinct phases. In Phase I, the Riyadh Governorate Complex and buildings in Phase 1, completed in 1992, included the construction of the Great Mosque and the Justice Palace, as well as public squares, gates, towers, parts of the old wall, public streets and some office and commercial facilities. This network of buildings, squares and arcades forms an urban complex in an indigenous environment.

The CITY:

Riyadh, one of the fastest growing cities in the world today, it was only a village in the Arabian province of Najd when it became the capital of the Saud family in 1810. Until the 1940s it remained a small fortress town, but since then its area has expanded 100- fold and its population grown from 25,000 to over three million.

What is now the center of Riyadh comprised almost the entire city in 1930. It was a provincial town of adobe structures enclosed by a wall. When Abdul Aziz became king of Saudi Arabia in 1932, he made his native Riyadh the nation’s capital and almost immediately began to develop the city beyond the old walls. That development remained local in materials and technology, however; it was not until the nineteen-fifties, when Abdul Aziz’s successor, Icing Saud, moved the government bureaucracy to Riyadh, that a huge program of modern development was mounted, and the city changed from a traditional provincial town to a Western-style city of automobiles and high-tech.

THE ARCHITECTURAL CHARACTER OF THE CITY

The traditional Najdi style of architecture is characterized by simple adobe or mud houses designed to provide insulation against the fierce heat of summers and bitter winds of winter. Decorative elements are limited to crenellations, moldings, and elaborate finials rendered in mud and then plastered or whitewashed. Roofs are flat and consist of tamarisk tree trunks plastered with mud. This traditional style of building was virtually wiped out by the growth of the new city, which features a panoply of new steel and concrete structures built in a ubiquitous international style.

THE REVITALIZATION PROGRAM:

The Qasr al-Hokrn District Development Program was conceived to revitalize the central core of the old city of Riyadh. This program was carried out by the Arriyadh Development Authority (ADA), which set out to balance new construction and the preservation of traditional elements. This project was conceived in two distinct phases. In Phase I, the Riyadh Governorate Complex and buildings and phase 11, completed in 1992.

THE COMPETITION

Originally the project included only the main mosque, the administrative center, and some commercial areas. After evaluating the conditions there, we concluded that it would be very difficult to carry out any coherent plan in the area given. It would probably have been sufficient for a project involving a single building, but not for developing the area in a way that would meet the expectations that the administration had. So we went back to the High Commission and were given a more reasonable delineation of space in which a designer could define the problems and suggest solutions.

ON SITE ISSUE

· Car ownership had also increased to the point where the open spaces in the city had disappeared, and still more parking places were needed. first decision was to limit automobile traffic in the old city. There was really no need for cars there, and they shorten the life of mud buildings certainly as much as do inappropriate uses such as commercial storage. The mosque was by that time an island in a sea of cars.

· It was not possible to restore the old city, since too many structures had been destroyed or were beyond repair. In addition, the mosque was not really a very fascinating monumental piece, although its setting was typical of Muslim cities, with shops around it and a main open space, and it reflected how the society had functioned under the economic and building constraints of an earlier time.

· The land value in the area is not only the highest in the city, but probably among the highest in the Middle East – in some areas as much as 100,000 Saudi riyals or $30,000 per square meter. Any program we suggested was bound to be opposed by people who had a lot of money tied up in the area.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.