Gothic Art and Architecture consists of religious and secular buildings, sculpture, stained glass, and illuminated manuscripts and other decorative arts produced in Europe during the latter part of the Middle Ages (5th century to 15th century). Gothic art began to be produced in France about 1140, spreading to the rest of Europe during the following century.

The Gothic Age ended with the advent of the Renaissance in Italy about the beginning of the 15th century, although Gothic art and architecture continued in the rest of Europe through most of the 15th century, and in some regions of northern Europe into the 16th century.

Early in the 12th century, masons developed the ribbed vault, which consists of thin arches of stone, running diagonally, transversely, and longitudinally. The new vault, which was thinner, lighter, and more versatile, allowed a number of architectural developments to take place.

A typical ribbed vault

The architects of the cathedrals found that, since the outward thrusts of the vaults were concentrated in the small areas at the springing of the ribs and were also deflected downward by the pointed arches, the pressure could be counteracted readily by narrow buttresses and by external arches, called flying buttresses. Consequently, the thick walls of Romanesque architecture could be largely replaced by thinner walls with glass windows, and the interiors could reach unprecedented heights.

A flying buttress

Gothic cathedral in Palma, Spain.

Flying buttress at Amiens Cathedral, France

During the first half of the 12th century, Gothic rib vaulting appeared sporadically in a number of churches. The particular phase of Gothic architecture that was to lead to the creation of the northern cathedrals, however, was initiated in the early 1140s in the construction of the chevet of the royal abbey church of Saint-Denis, the burial church of the French kings and queens near the outskirts of Paris. In the ambulatory of Saint-Denis, the slim columns supporting the vaults and the elimination of the dividing walls separating the radiating chapels result in a new sense of flowing space presaging the expanded spaciousness of the later interiors.

The addition of an extra story to the traditional three-story elevation of the interior increased the height dramatically. This additional story, known as the triforium, consists of a narrow passageway inserted in the wall beneath the windows of the clerestory (upper part of the nave of a church, containing windows) and above the large gallery over the side aisles. The triforium opens out into the interior through its own miniature arcade.

The complexities and experiments of this early Gothic period were finally resolved in the new cathedral of Chartres (begun 1194). By omitting the second-story gallery derived from Romanesque churches but retaining the triforium, a simplified three-story elevation was reestablished. Additional height was now gained by means of a lofty clerestory that was almost as high as the ground-story arcade. The clerestory itself was now lighted in each bay or division by two very tall lancet windows surmounted by a rose window.

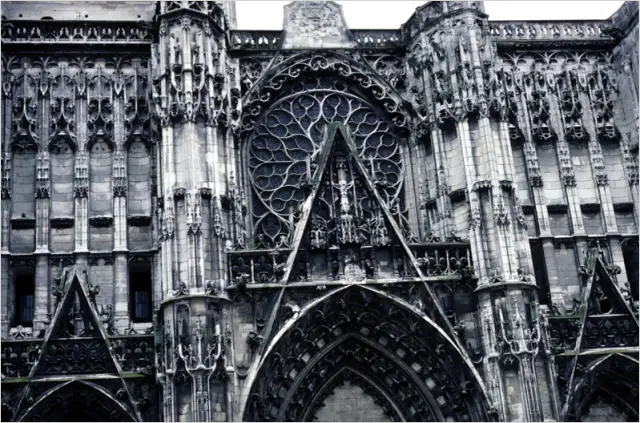

Exterior Facade

Interior of rose window

The High Gothic period, inaugurated at Chartres, culminates in the Cathedral of Reims (begun 1210). Bar tracery was an invention of the first architect of Reims. In the earlier plate tracery, as in the clerestory at Chartres, a solid masonry wall is pierced by a series of openings. In bar tracery, however, a single window is subdivided into two or more lancets by means of long thin monoliths, known as mullions. The head of the window is filled with a tracery design that has the effect of a cutout.

Reims cathedral , France

Another equally successful High Gothic solution to the problems of interior design occurs in the great five-aisled cathedral at Bourges (begun 1195). Instead of an enlarged clerestory, as at Chartres, the architect of Bourges created an immensely tall ground-story arcade and reduced the height of the clerestory to that of the triforium.

he brief interval of the High Gothic period is followed in the 1220s by the nave of Amiens Cathedral. Amiens provided a transition to the loftiest of the French Gothic cathedrals, that of Beauvais. By superimposing on a giant ground-story arcade an almost equally tall clerestory, the architect of Beauvais reached the unprecedented interior height of 48 m (157 ft).

Beauvais Cathedral

Beauvais was begun in 1225 before Louis IX, king of France, came to the throne. During his reign, Gothic architecture entered a new phase, known as the Rayonnant. The word Rayonnant is derived from the radiating spokes, like those of a wheel, of the enormous rose windows that are one of the features of the style.

Detail of Rose Window, Lincoln Cathedral

Height was no longer the prime objective. Rather, the architects further reduced the masonry frame of the churches, expanded the window areas, and replaced the external wall of the triforium with traceried glass. Instead of the massive effects of the High Gothic cathedrals, both the interior and the exterior of the typical Rayonnant church now more nearly assumed the character of a clear shell.

All these features of the Rayonnant were incorporated in the first major undertaking in the new style, the rebuilding of the royal abbey church of Saint-Denis. Of the earlier structure only the ambulatory and the west facade were preserved.

The spirit of the Rayonnant, however, is perhaps best represented by the Sainte-Chapelle, the spacious palace chapel built by Louis IX in the center of Paris. Immense windows, rising from near the pavement to the arches of the vaults, occupy the entire area between the vaulting shafts, thus transforming the whole chapel into a sturdy stone armature for the radiant stained-glass windows.

Saint Chapelle Cathedral, Paris

n the evolution of Gothic architecture, the progressive enlargement of the windows was not intended to shed more light into the interiors, but rather to provide an ever-increasing area for the stained glass. As can still be appreciated in the Sainte-Chapelle and in the cathedrals of Chartres and Bourges, Gothic interiors with their full complement of stained glass were as dark as those of Romanesque churches. The dominant colors were a dark saturated blue and a brilliant ruby red.

Wall stained-glass medallions illustrating episodes from the Bible and from the lives of the saints were reserved for the windows of the chapels and the side aisles. Their closeness to the observer made their details easily distinguishable.

Each of the lofty windows of the clerestory, on the other hand, was occupied by single monumental figures. Because of their often colossal size, they were also readily visible from below.

.

Bamberg Rider, Germany

In France, late Gothic architecture is known as flamboyant, from the flamelike forms of its intricate curvilinear tracery. The ebullient ornamentation of the flamboyant style was largely reserved for the exteriors of the churches. The interiors underwent a drastic simplification by eliminating the capitals of all the piers and reducing them to plain masonry supports. All architectural ornamentation was concentrated in the vaults, the ribs of which formed an intricate network of even more complicated patterns

.

Troyes Cathedral, France

Flamboyant architecture originated in the 1380s with French court architect Guy de Dammartin. The great surge in building activity, however, came only with the conclusion of the Hundred Years’ War in 1453, when throughout France churches were being rebuilt in the new style. Flamboyant architecture produced its most extravagant intricacies in Spain.

In Portugal, during the reign of King Manuel I, it developed into a national idiom known as the Manueline style, marked by a profusion of exotic motifs.

Santa Maria Chapel at Belem, Portugal

Spurning the flamboyant style altogether, the English builders devised their own late Gothic architecture, the Perpendicular style. The use of a standard module consisting of an upright traceried rectangle, which could be used for wall paneling and window tracery alike, resulted in an extraordinary unity of design in church interiors.

The masterpiece of the style, the chapel of King’s College in Cambridge, achieves a majestic homogeneity through the use of the new fan vaulting, the fan-shaped spreading panels of which are in complete accord with the rectangular panels of the walls and windows.

Detail Of Fan Vault, King’s College Chapel

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.